Impedance

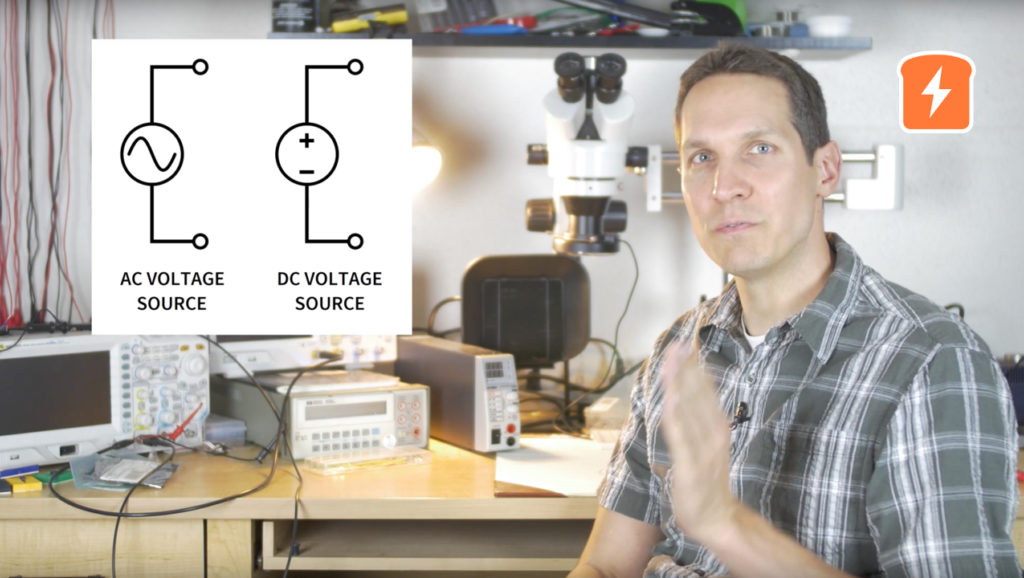

How much a device will oppose, or resist, both DC and AC current.

Represents the opposition that the circuit exhibits to the flow of sinusoidal current.

Fundamentals of Electric Circuits, 5th Edition by Charles K. Alexander and Matthew N. O. Sadiku

The total opposition to the flow of current in a sine-wave ac circuit.

Grob’s Basic Electronics, 11th Edition by Mitchel E. Schultz

Mechanical impedance is a measure of how much a structure resists motion when subjected to a harmonic force. It relates forces with velocities acting on a mechanical system. The mechanical impedance of a point on a structure is the ratio of the force applied at a point to the resulting velocity at that point.[1][2]

Mechanical impedance is the inverse of mechanical admittance or mobility. The mechanical impedance is a function of the frequency w of the applied force and can vary greatly over frequency. At resonant

frequencies, the mechanical impedance will be lower, meaning less force

is needed to cause a structure to move at a given velocity. A simple

example of this is pushing a child on a swing. For the greatest swing

amplitude, the frequency of the pushes must be near the resonant

frequency of the system.

Where F is the force vector, v is the velocity vector, Z is the impedance matrix and w is the angular frequency

Mechanical impedance is the ratio of a potential (e.g. force) to a flow (e.g. velocity) where the arguments of the real (or imaginary) parts of both increase linearly with time. Examples of potentials are: force, sound pressure, voltage, temperature. Examples of flows are: velocity, volume velocity, current, heat flow. Impedance is the reciprocal of mobility. If the potential and flow quantities are measured at the same point then impedance is referred as driving point impedance; otherwise, transfer impedance.

- Resistance - the real part of an impedance.

- Reactance - the imaginary part of an impedance.